History of Corn

Where did corn come from?

Corn, also called maize, is the most widely planted domesticated crop on Earth. While other plants, such as strawberries, have wild counterparts, corn does not. When humans discovered and learned to enjoy eating plants like strawberries, we started growing them and adapting them to domesticated farming conditions, but they continued to loosely resemble their wild relatives. With corn however, nowhere in nature can you find anything even similar. Why is that? Where did corn come from?

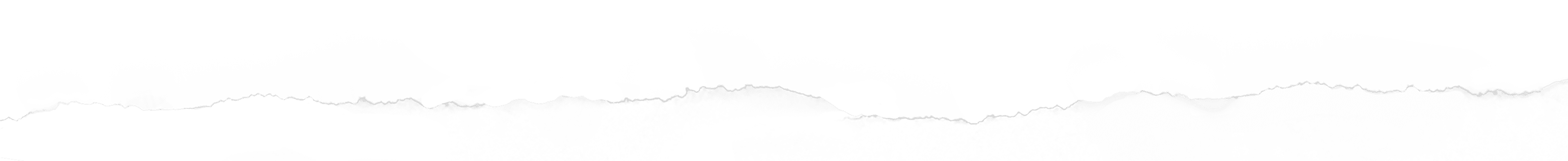

Many people assumed the “wild” variety of corn died out, and that is why it wasn’t found in nature anymore. George Beadle, an American geneticist, proved otherwise. He found it was possible to breed corn from a wild grass called teosinte.

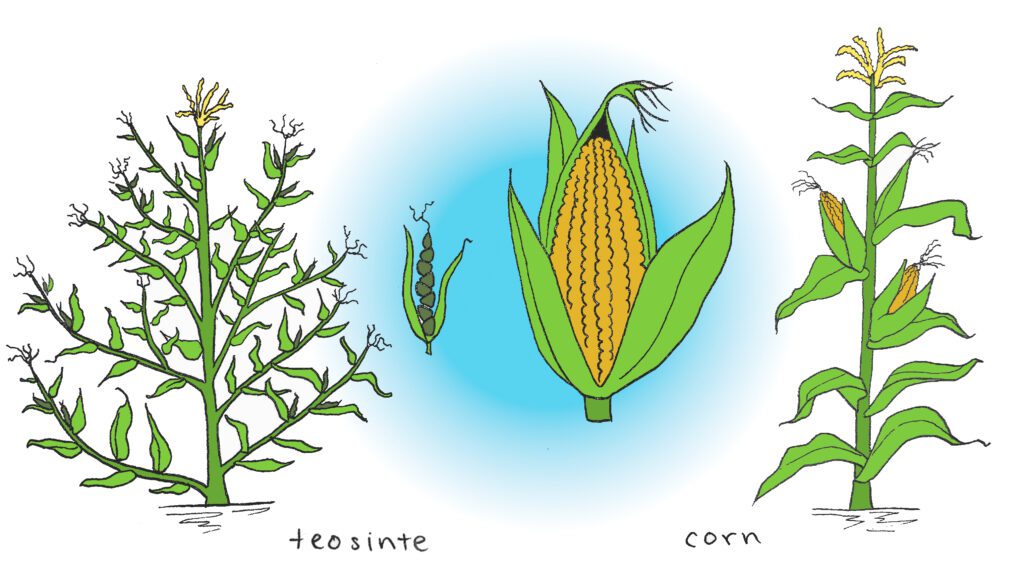

With this knowledge, scientists started to dig deeper into how teosinte could evolve into corn. By breeding them together hundreds of times and comparing physical characteristics, they concluded that only 4 or 5 genes actually changed between the two plants, explaining why they were still able to create offspring with one another. To find out where these mutations came from, a corn genome was compared to many different teosinte genomes from across Mesoamerica. Geneticists found modern-day corn to be the most closely related to teosinte found in the Balsas River Valley, or present-day Southern Mexico. Also, because there is naturally a typical “rate of mutation” of genes, and there were 4-5 mutations, they predicted corn was first developed from teosinte in the Balsas River Valley approximately 9000 years ago, presumably by the Native Americans.

But this was not enough for the scientists: they wanted hard evidence. Working with archeologists in Latin America they investigated the Balsas River Valley. With the help of locals, a cave was discovered containing ancient grinding stones. These stones revealed microscopic evidence of corn, carbon dated to approximately 8700 years ago that also supported the genetic evidence suggested! Therefore, it is easy to conclude that people in present-day Mexico initially bred domesticated modern corn and from there it spread across the Americas.

Native American Culture

As civilizations established and flourished in the Americas, so did maize. Many different varieties were developed that were able to survive in starkly different locations and climates, from present-day Illinois to Peru. During the course of thousands of years, Native Americans developed advanced agricultural techniques. The most well-known is called the Three Sisters. This was a method of planting three crops – squash, beans, and corn – on the same plot of land. The three plants worked together: corn acted as the stalk for the beans to climb, the beans fertilized the soil, and the squash leaves prevented weeds from growing on the ground. This meant the Native Americans did not have to rotate crops as we do today since the soil remained healthy and full of nutrients. Various Native American cities and groups utilized different methods of agriculture for their different climates and needs; however, corn played a central role in agriculture, and the Three Sisters demonstrates that.

The significance of corn in these civilizations can also be seen in many Native Americans’ cultures and religious beliefs. The Mayans believed, for example, the first humans were made from corn. Yum K’aax, the Mayan maize god, was their creator, and the Mayans protected him by protecting their crops. The Aztecs had a similar maize god, Centeotl. It’s predicted that both of these Gods stemmed from an earlier Olmec maize god. With a heavy dependence on corn, Mesoamerican cultures were only possible because of their mastery of the grain, which is why their cultural beliefs tended to reflect that.

The World

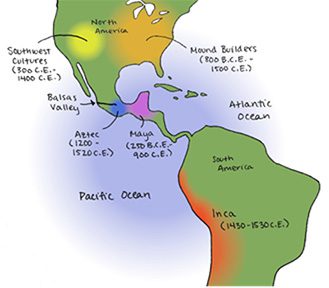

After corn became central to Native American civilizations, Europeans arrived in the Americas. Despite being exposed to new crops, corn remained a constant in these civilizations. The Europeans appreciated the value of corn and brought it back to Spain, where it spread throughout Europe in the 1500s. From there, the slave and spice trade brought corn to Africa, India, and East Asia. Because of corn’s incredible adaptability, it took hold in a variety of climates and is a staple crop throughout the globe to this day.

With hundreds of varieties of corn existing in the Americas, several types of corn were introduced in other parts of the world. Africa, for example, grows predominantly white corn, whereas in Asia, people prefer darker yellow corn. This is presumably because these were the types of corn they were introduced to, and the kinds of corn that grew well in their particular climate.

The Green Revolution

Starting in the 1950’s, there was a concerted international effort to promote the adoption of modern farming practices and new high-yielding varieties of corn and other staple crops to increase food production in the global south. This “green revolution” was largely successful and contributed to widespread reductions in poverty and helped avert hunger for millions. It also produced some less desirable consequences however, including pollution from agrochemicals and a reduction in dietary diversity as many populations became increasingly dependent on a single staple crop. In many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa the primary staple crop became white corn, which provides calories in abundance, but is short on many other nutrients. This lack of dietary diversity and dependence on white corn in turn contributed to the development of severe micronutrient deficiencies.

Following the green revolution is what some call the “gene revolution” which sought to introduce new genetically modified varieties to further improve agricultural productivity. While these varieties had been largely successful elsewhere, a distrust of these new technologies and the multinational corporations that develop them has led to only a handful of countries in sub-Saharan Africa approving their use.

The “Orange Revolution”

Looking to help address malnutrition in Africa without the use of GMOs, Professor Torbert and his colleagues went back to the basics: hand selection. The Native Americans did it with teosinte: selecting the plants that displayed the characteristics they valued. Eventually, after many generations of selection, the cobs slowly increased in size, the kernels became softer, and the color turned from white to yellow. On a fundamental level it’s the same process Professor Torbert used to develop his Orange Corn. He saw Vitamin A deficiencies in parts of Africa, recognized they ate mostly white corn, and decided to breed corn high in antioxidant carotenoids that could provide Vitamin A to help them get this essential nutrient. It’s easy to see the carotenoids in corn since they are the natural antioxidant pigments that provide its yellow color. The more yellow color, the more carotenoids. Therefore, Professor Torbert bred his corn to make it as yellow as possible, and with each generation it became more and more yellow. Eventually, he made it so yellow it turned orange!

Throughout history, corn has been utilized in various ways, leading to its importance today. Nine thousand years after the Native Americans developed corn in Mexico, Professor Torbert was able to create Orange Corn in Indiana, with the exact same method. An ancient method used on a plant in Mesoamerica was utilized on the same plant thousands of years later to help give people across the globe the nutrition they need to live healthier lives.

More resources on the history of corn:

TedEd Video – The history of the world according to corn

HHMI BioInteractive – Popped Secret: The Mysterious Origin of Corn

GMOsafety – History of Maize Cultivation

ThoughtCo. – The Gods of Olmec

Trama Textiles – Maize: The Epicenter of Maya Culture

ThoughtCo. – Centeotl, The Aztec Corn God (or Goddess)

University of Illinois Library – World map of spread of corn